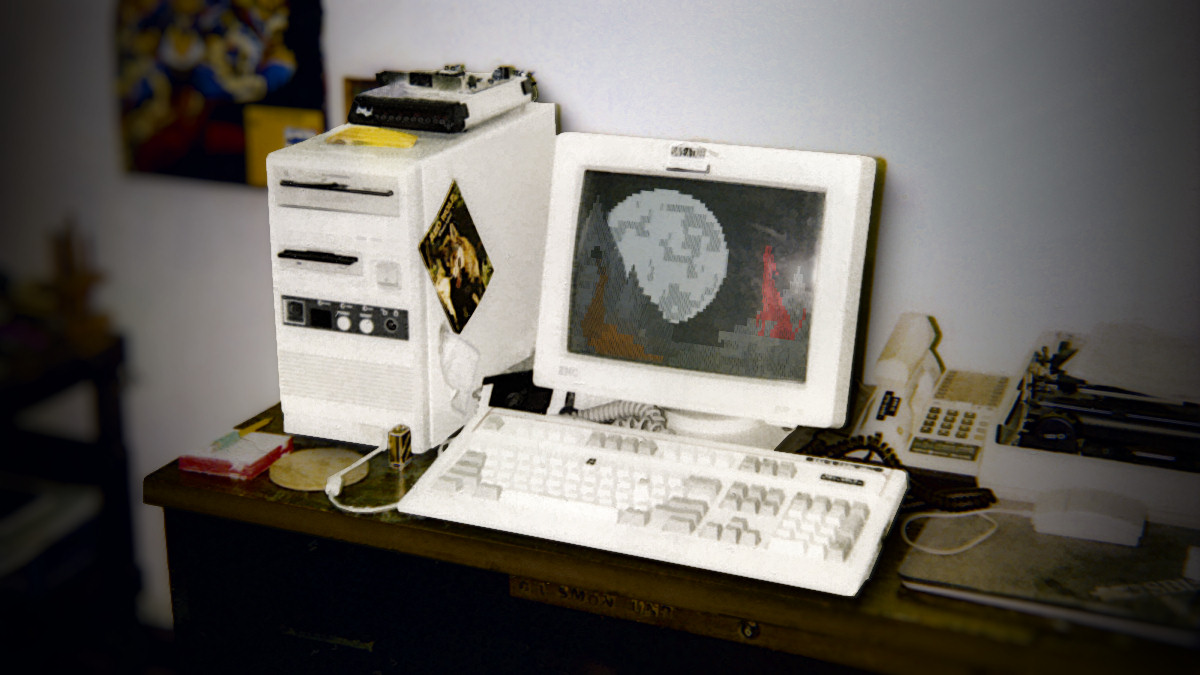

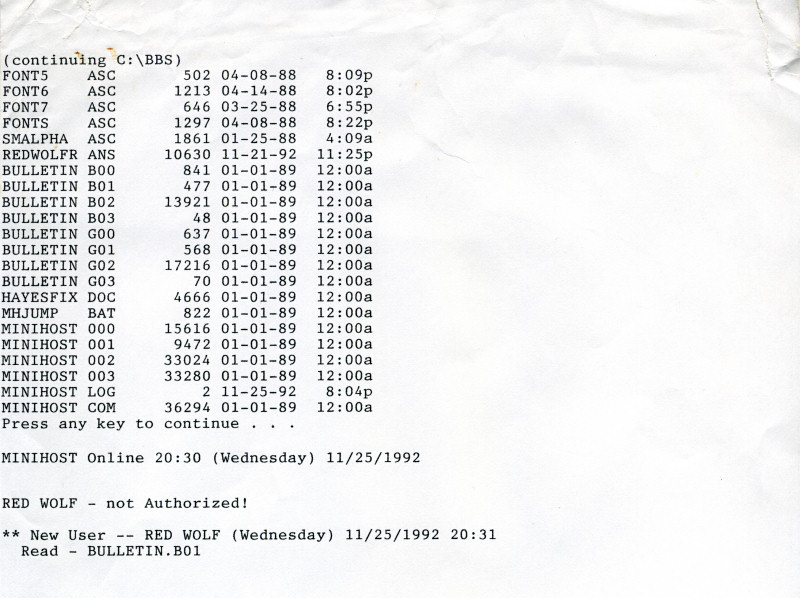

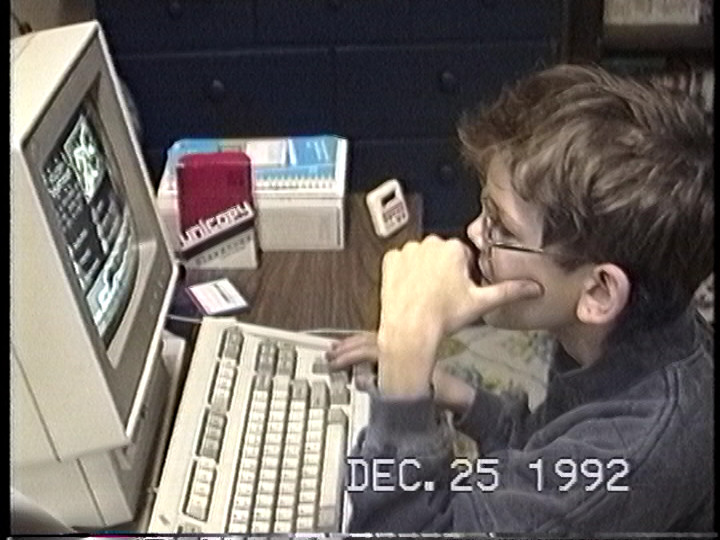

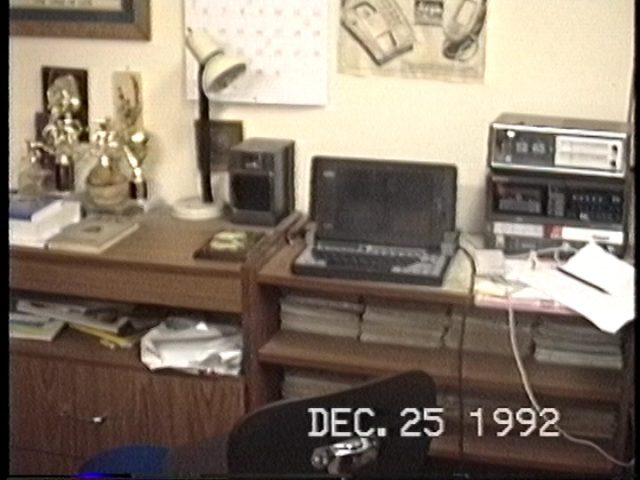

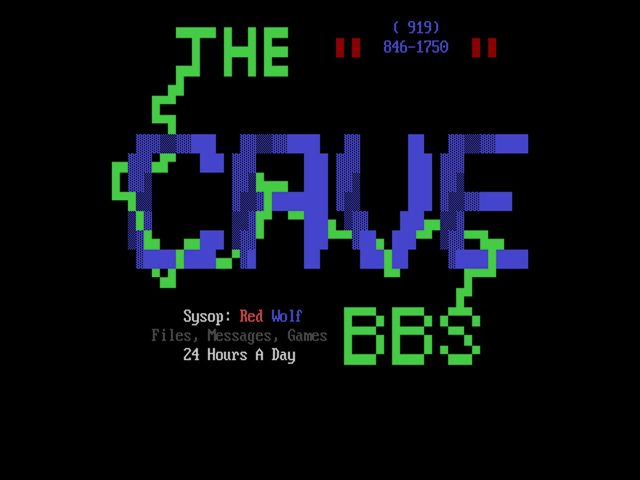

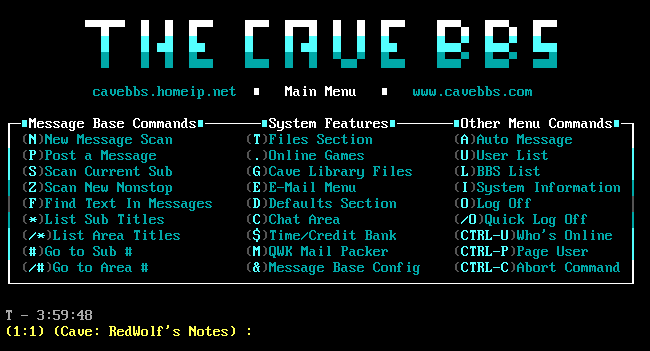

Thirty years ago last week—on November 25, 1992—my BBS came online for the first time. I was only 11 years old, working from my dad's Tandy 1800HD laptop and a 2400 baud modem. The Cave BBS soon grew into a bustling 24-hour system with over 1,000 users. After a seven-year pause between 1998 and 2005, I've been running it again ever since. Here's the story of how it started and the challenges I faced along the way.

Enter the modem

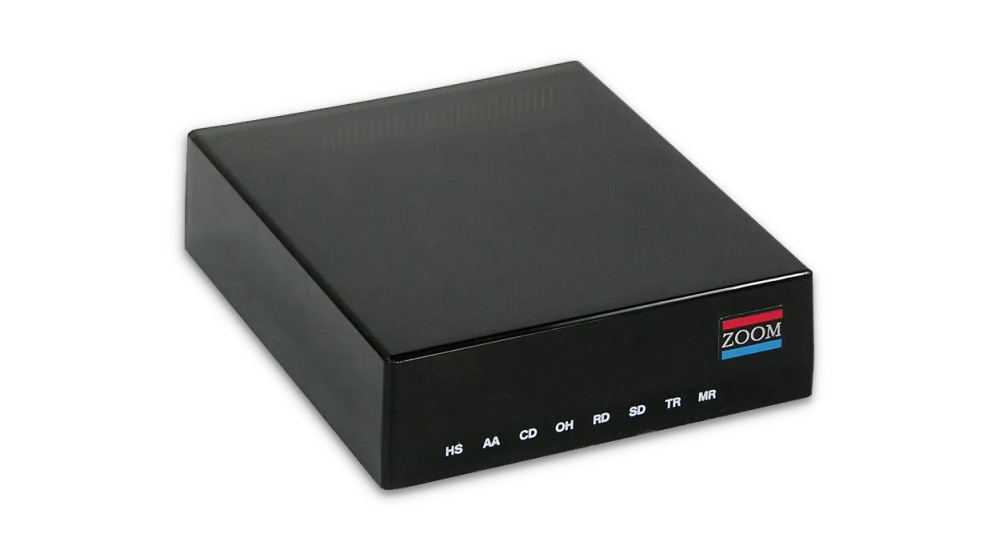

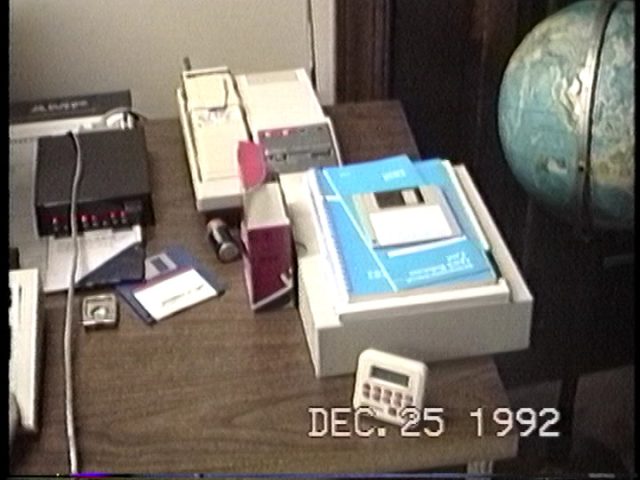

In January 1992, my dad brought home a gateway to a parallel world: a small black plexiglass box labeled "ZOOM" that hooked to a PC's serial port. This modem granted the power to connect to other computers and share data over the dial-up telephone network.

While commercial online services like CompuServe and Prodigy existed then, many hobbyists ran their own miniature online services called bulletin board systems, or BBSes for short. The Internet existed, but it was not yet widely known outside academic circles.

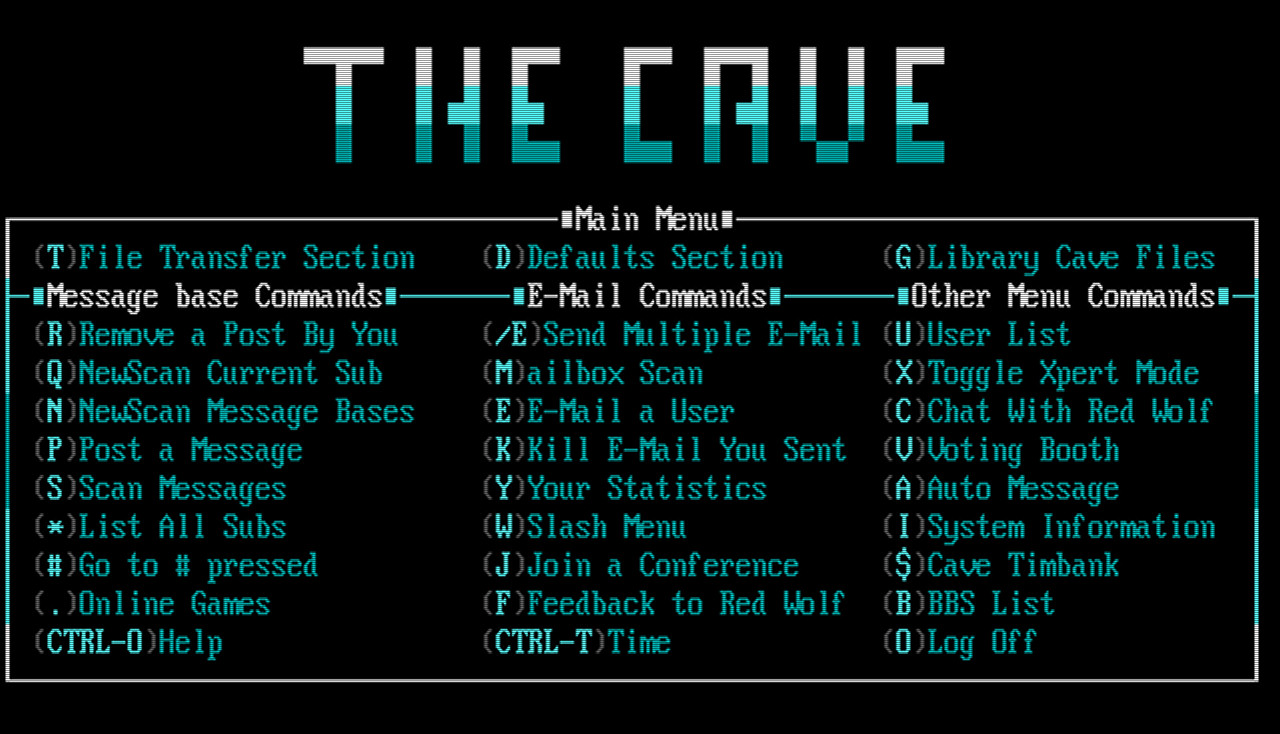

Whereas the Internet is a huge connected web of systems with billions of users, most BBSes were small hobbyist fiefdoms with a single phone line, and only one person could call in and use it at a time. Although BBS-to-BBS message networks were common, each system still felt like its own island culture with a tin-pot dictator (the system operator—or "sysop" for short) who lorded over anyone who visited.

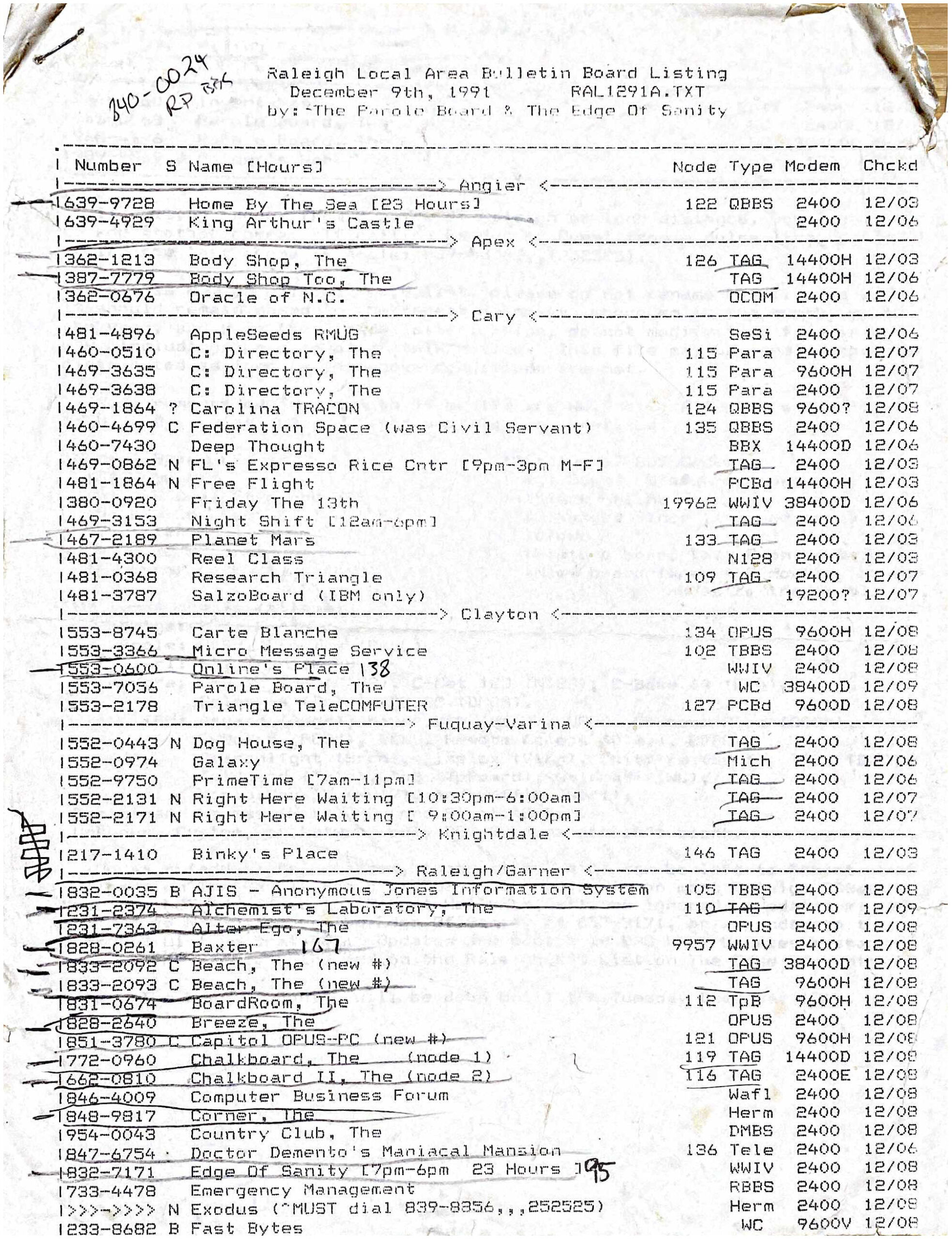

Not long after my dad brought home the modem, he handed off a photocopied list that included hundreds of BBS numbers from our 919 area code in North Carolina. Back then, the phone company charged significantly for long-distance calls (which could also sneakily include parts of your area code), so we'd be sticking to BBSes in our region. This made BBSes a mostly local phenomenon around the US.

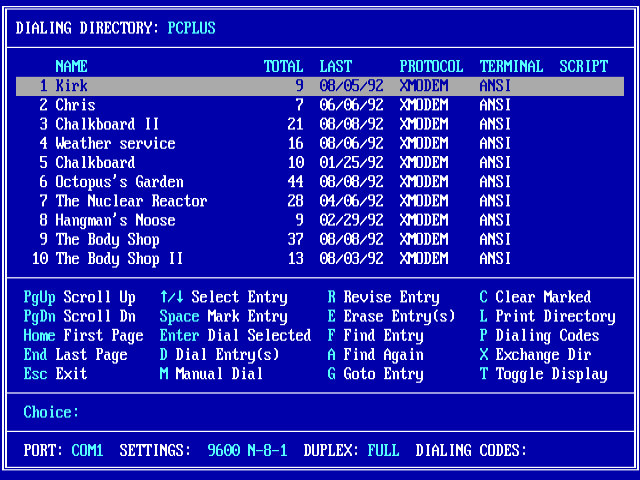

With modem in hand, my older brother—about five years older than me—embraced calling BBSes first (we called it "BBSing"). He filled up his Procomm Plus dialing directory with local favorite BBSes such as The Octopus's Garden, The Body Shop, and Chalkboard. Each system gained its own flavor from its sysop, who decorated it with ANSI graphics or special menus and also acted as an emcee and moderator for the board's conversations.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...